Despite decades of band culture, new research suggests that the golden era of the British band may be behind us.

From the Beatles to One Direction, the Spice Girls to Take That, bands are a stalwart of the British music scene. If you’re of a certain age, these names need no introduction. They are the sounds, faces, and albums that have defined British culture for decades. Where would Christmas be without Wham!? Or rock music without the Rolling Stones? Where would summer festivals be without Brit Pop?

According to new research, the last 30 years have seen band culture almost entirely replaced by solo stars and one-time collaborations. The hysteria that surrounded the Beatles is now reserved for Taylor Swift. The glory days of One Direction have been replaced by Beyonce. It’s been decades since the heyday of British bands at the top of the charts – but why?

When did bands start to lose out to solo artists? And when did collaborations enter the picture?

To answer these pressing questions, Skoove teamed up with the research experts at DataPulse Research. Together, the team analyzed decades of chart history to pinpoint exactly when solo stars began to eclipse band culture – and the reasons behind that shift.

The glory days of British bands have waned over the last two decades

Some of the biggest names in British music are bands – but they are overwhelmingly from years past.

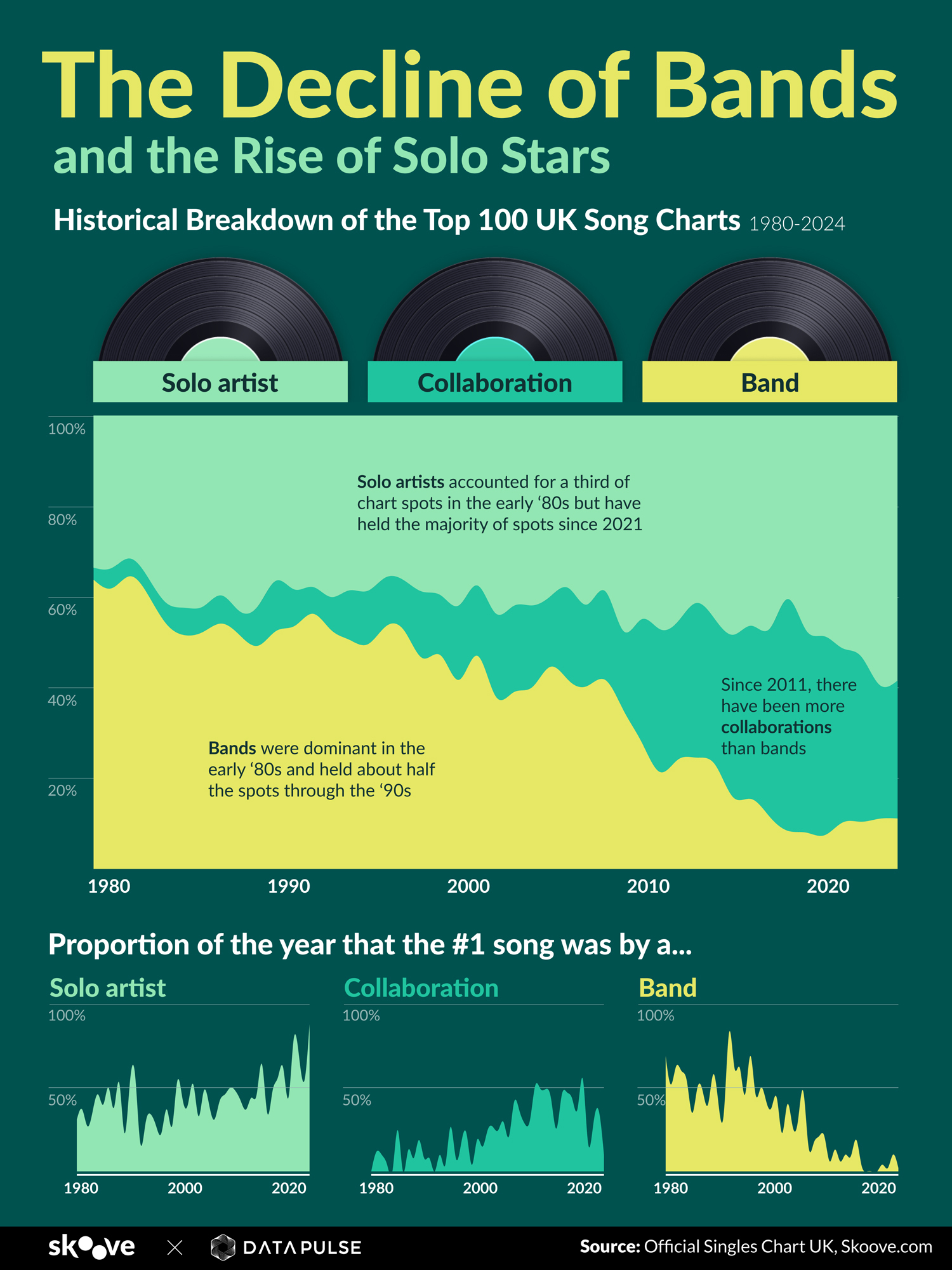

Our study of the UK charts from October 1980 – October 2024 has confirmed a consistent decline in the presence of bands at the top of musical charts. At the same time, solo artists have dominated. Perhaps that’s no surprise. Afterall, the UK pop industry has historically produced hundreds of successful solo artists, many of which have come from bands, for instance Robbie Williams, Sting, George Michael, Phil Collins, Harry Styles just to name a few.

It isn’t just solo stars that are stealing the spotlight. A new genre has also emerged to challenge the dominance of bands in recent years. Collaborations are also increasing in popularity, trending more often in chart positions and snatching airplay, streaming and chart placement from bands.

“It’s perhaps inevitable that collabs have become so popular. They bring double the star-power of solo artists, allowing each star to tap into their own and their collaborator’s audience. It’s a great way to increase exposure, grow streams and reach new demographics. There’s also the novelty factor to consider. As collaborations tend to only happen every once in a while between specific stars, they’re inherently more valuable and more desirable to listeners.”

Bands are no longer making the charts as often as solo stars

There were 223,030 individual song placements on the weekly top UK charts between October 1980 and October 2024, each song was given the value of either band, solo musician, or collaborator. Of all the total song placements, 37% were bands, 20% were collaborations, and 43% were solo artists.

The data was then skewed to interpret songs in the dataset as single individual songs regardless if they made the charts for just a week or appeared on the list multiple weeks at a time. This brought the sample set down to 37,941 songs, of which 44% were bands, 16% were collaborations, and 40% were solo artists.

The question is, why are listeners turning off bands and turning up the likes of Taylor Swift and Beyonce?

There are multiple reasons solo stars are shining brighter

There’s no one reason why solo artists are eclipsing bigger bands. Instead, multiple events have created the perfect storm.

Streaming technology has changed how we discover and listen to music

In years past, new bands would be discovered on the front covers of magazines, on the radio and on TV. The launch of streaming platforms like Spotify (2008) and Apple Music (2015) has changed all that. While the exact details of how algorithms choose which artists to spotlight and feature in curated playlists are proprietary, it’s indisputable that Spotify listeners in particular heavily favor solo artists and collaborations. It’s no coincidence that there isn’t a single band featured in either the top 10 most streamed songs or top 10 artists globally for 2024.

“It’s no coincidence that the decline of bands has coincided with the growing popularity of Spotify and Apple Music,” Schirmer says. “Until rock bands can crack the streaming puzzle, it’s very unlikely we’ll see bands topping the charts. That’s a challenge that both bands and their record companies will need to take seriously if we’re to resurrect rock ‘n’ roll from the annals of history.”

Band dynamics tend to be challenging

Band dynamics can be tricky. There are multiple big personalities (and big egos) to manage. Not everyone can have star billing. Not everyone has the same star power. Conflicts and creative differences are inevitable.It’s pretty much inevitable that there’ll be a major falling out. Or one band member wanting to go a different way.

Even the biggest bands in the world fall victim to in-fighting and clashing personalities. The Eagles broke up in 1980 after a spat between lead singer Glenn Frey and guitarist Don Felder. Not even family ties could stop Oasis from imploding. And as The Pussycat Dolls found out, there can only really be one star.

It’s much easier for labels to manage solo artists.. It’s simpler to coordinate, less drama and a whole lot cheaper. Plus, it’s always clear where the spotlight should shine.

Solo artists are pros at using social media to build their brand

Justin Bieber might be the first social media success story in the music biz, but he certainly won’t be the last. Younger generations are masters at influencing, thanks to the growing popularity of platforms like TikTok and Instagram. It’s much easier for individual personalities to stand out and gain mass appeal on an in-stream video or in-feed post, with many emerging stars doing just that.

“The impact of social media can't be understated. It has been absolutely instrumental in changing how solo artists break through - no longer are they reliant on being discovered by a music executive. They can tap into this enormous global audience and create their own communities of loyal fans to raise awareness and build momentum way before they’re on the radar of labels” adds Schirmer.

“We’ve seen many solo artists in recent years use extremely sophisticated social media strategies to launch their careers by parlaying that grassroots, online support into mainstream success. Let’s not forget, streaming platforms and social media go hand-in-hand. Once they have that bit of traction and popularity on social media, it’s easy to begin driving downloads with a link.”

Bands fall off the charts faster than solo artists and collaborators

UK band culture between the 80s and 90s influenced the entire Western world with the constant reimaginings of youth culture between phases of punk, new wave and Britpop. In the UK charts bands accounted for more than 60% of the song placements between 1980 and 1983, and hovered around 50% of the placements from 1984 to 1999.

From this point on, bands went into a precipitous decline, going from 47% in 1999 to just 7% in 2021. In the last four years, they’ve accounted for about 10% of the charts. Solo artists saw the opposite trend, moving from about a third of the spots on the music charts in the early 80s to around 40% of the charts between 1984 and 2008. Is it a coincidence that Spotify launched in 2008? Perhaps not.

In 2009, solo artists claimed 48% of the chart spots and have been on the rise ever since, reaching as much as 59% of the placements in 2023 and 2024.

The big surprise of this study is just how much the category of collaborations has filled the void left by bands. Through the ‘80s and early ‘90s, they accounted for less than 10% of the charts. This was the time of Oasis, Pulp, The Happy Mondays. Collabs weren’t a thing.

With the disappearance of those bands, collaborations have emerged as a genre to fill the void. They dominated the charts in 2017-2020, accounting for 40% of the charted songs, including a high in 2018 (51% of the charted songs).

Bands aren’t able to knock solo stars off the top spot

In the last 18 years (since 2007), bands have struggled to secure a #1 hit in the UK. During that period, they’ve captured the top spot less than 20% of the time (10 weeks out of 52), except in 2009 and 2010 where they managed 11 weeks of the year. The downfall is cemented when we see bands that didn't hold the spot for any of the weeks in 2018, 2019, and 2020.

Historically in the UK charts, solo artists have held the top spot between 25%-50% of the time. So, solo success is nothing new - but it is beginning to dominate. In six of the last seven years, solo artists like Taylor Swift and Miley Cyrus have held the top spot for more than half of the weeks. In 2024 alone, that figure is increasing. From January to October, solo artists occupied the #1 spot 88% of the time. That leaves very little time or space for bands to make their mark.

Making it even harder for bands to get a foothold is the increasing popularity of collaborations. In the 80s and 90s, collabs claimed top spot just 10% of the time. In the last 20 years, that number has increased to 34%. Elton John’s The Lockdown Sessions is a case in point. His collaborations with Britney Spears and Dua Lipa were the soundtrack to lockdown for many British households, a bright point in an otherwise dark time.

Band hits don’t have the same level of stickiness as solo stars

How often in the run up to Christmas did you listen (willingly or otherwise) to “All I Want for Christmas”? If you saw Mariah in her Santa outfit more often than you saw your family between Halloween and December, you aren’t alone. But how many recent songs from bands can you think of that crop up with such regularity? Likely, none.

Looking at all 37,941 unique songs on the charts over the last 45 years, 3% (1,186) have what is called extreme stickiness, meaning they have appeared on the charts for 25 or more weeks.

These songs generally fall into two categories; either decades-long seasonal classics, such as Mariah Carey’s “All I Want For Christmas Is You,” which has made the weekly charts 131 times in its yearly serenade in the December charts, or songs with consecutive-week runs like The Killers’ “Mr. Brightside,” which has made the list some 430 times.

If we look at total songs compared with sticky songs, it’s clear that while bands account for the largest number of unique songs (44%) on the charts, they make up just 22% of the long-running songs. On the other hand, collaborations and solo artists punch above their weight, having the most increased stickiness, being 16% of all charted songs while hitting 32% of the sticky ones. Solo artists likewise see an increase, going from 40% of all charted songs to representing 49% of the sticky ones.

What will happen to rock music?

Will we ever see a new Rolling Stones? Or Queen? Will there be a Guns N’Roses 2.0? The data says not likely. That’s because the decline of bands also means the decline of rock music in general.

Schirmer explains, “There’s an intrinsic link between the success of bands and the proliferation of rock music. So many bands have their roots in rock - so when one struggles, the other also falters. The worry of course is that as bands continue to see their audiences drift away and streaming and air time limited, rock as a genre is also disappearing from the airwaves.”

The graph below shows how many bands make up the rock genre on the top 500 artists on Spotify, with solo artists accounting for 74% of the monthly listeners and bands making up 26%.

As bands are most heavily concentrated in the rock category, it’s fair to say that rock music could become a thing of the past, especially as rock music isn’t as popular as pop, or hip-hop.

With little streaming success, there’s little incentive for labels to create new bands or invest resources in marketing existing bands, further fuelling the decline of bands and by extension, rock music itself.

Conclusion

The popularity of bands has been waning for decades, thanks to a perfect storm of factors; from the ease with which solo artists can release new music to the lower cost and less complex logistics. There’s no travel conflicts, differing musical tastes or competing egos for record labels to grapple with when there’s just one star to handle.

To halt the decline, bands keen to taste chart success will need to take a leaf out of their solo rivals’ playbook. Becoming better at using platforms like TikTok and Instagram to win over new fans and promote their new music could be a game changer. Likewise, deploying platforms and social tactics which create better levels of engagement - such as hosting Insta lives, Hangouts and even using Patreon - could create more awareness of new music. In turn, this would increase band downloads and streaming, putting them back in contention for chart positions.

Methodology

This study is largely based on the UK’s weekly charts from October 1980 to October 2024. Over this 45-year period, charts included 100 song placements every week (with the exception of periods in the early 1980s and early 1990s that had 75 top songs). In total, 223,030 songs were in the database. The analysis ran as follows:

- All songs were tagged as either bands, collaborations or solo artists. (Collaborations can be two artists or a band featuring an artist.)

- From this, the team calculated the percentage of songs by bands, by collaborators and by solo artists every week, month, and year. Every weekly chart is independent, so songs that appeared over multiple weeks would be counted as many times as they appeared.

- In addition to analyzing overall chart patterns, the team looked at mega hits. For each of the 52 weeks in every year, the team tallied whether the top-played song was by a band, a collaborator, or a solo artist. From that data, they calculated the share of #1 hits each year that fell into the three categories.

- Finally, the team looked for “stickiness,” or how many weeks a song appeared on the charts. The team tracked each song’s placement on the charts week by week. In total, there were 37,941 unique songs on the charts over the last 45 years. The team found 1,186 of the songs had “extreme stickiness,” meaning they have appeared on the charts for 25 or more weeks. Note: Some songs, including Christmas songs, appeared on and off over the years while others had long runs on the charts. Among the “sticky” group, the team calculated the percentage that were tagged as bands, collaborations, or solo artists.

To incorporate streaming data, the study also analyzed popular songs on Spotify based on a ranking by the number of listeners on Chartmasters.

- Songs were tagged as either bands or artists. Songs were also tagged by musical genre.

- The team organized the songs in groups of 100 (the top 100, followed by the top 101-200, and so on.)

- The team analyzed the share of songs by bands and by artists for the top five genres (pop, rap/hip-hop, rock, latin, electronic) and “other” genres, up to the 500th most popular song.

Author of this blog post:

Susana Pérez Posada

With over seven years of piano education and a deep passion for music therapy, Susana brings a unique blend of expertise to Skoove. A graduate in Music Therapy from SRH Hochschule Heidelberg and an experienced classical pianist from Universidad EAFIT, she infuses her teaching with a holistic approach that transcends traditional piano lessons. Susana's writings for Skoove combine her rich musical knowledge with engaging storytelling, enriching the learning experience for pianists of all levels. Away from the piano, she loves exploring new places and immersing herself in a good book, believing these diverse experiences enhance her creative teaching style.

Feel free to use this content

This content, including images and data visualizations, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. That means you are free to share, copy, and redistribute the material in any medium or format, and adapt, remix, transform and build upon the material for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you provide proper attribution. Please credit and link to: Skoove.com when using any part of this content.