Transposition is often shrouded in mystery, especially to piano players who haven’t been playing very long. Anyone who studies music theory will learn how to transpose music. People who play transposing instruments such as alto saxophone, clarinet or bass are already familiar with the concept.

If you’ve ever bought sheet music online, you may have noticed an option to choose what key you’d like the sheet music to be in.

What is music transposition?

A song is written in a certain key. For instance, B flat major, which has two flats. Key signatures link to playing scales in each key and within each key are musical modes.

As a transposition music definition, there are times when the key of a piece needs to be changed and each pitch moved either higher or lower – depending on the circumstances – by the same interval. When we change the key of the song, this is called transposing. Transposing music isn’t very difficult if you understand some transposition music theory.

Why do we need transposition?

Any song can be played in any key. What determines the key to be used is a number of factors which we will have a look at. Composers often have their favorite keys they tend to write in and singer/songwriters tend to write in keys they feel are in a good vocal range.

To make singing easier

One of the reasons we transpose songs is because a singer needs the melody in a better key for their voice. Let’s say a singer is practicing a song in the key of F major but the highest pitch in the song is above her comfortable singing range.

The song can be transposed down by any number of notes to a more comfortable range for her voice, to D major, or Db major, or any other key.

To make music easier to read

If you haven’t been reading music for very long you might feel intimidated looking at a piece of music with a key signature of several sharps or flats at the beginning of each line. If the same piece of music is transposed, the key can change to a much simpler one, making it much more manageable for a beginner or early intermediate piano player to cope with.

Generally in written music, the less accidentals we have to process, the better. So sometimes transposing to a key that results in less sharps, flats and naturals can make it easier to read.

Alto singers and viola players have music which is transposed into a different clef which looks like this:

The whole note you see on the middle line is middle C when using this clef. The pitch of the middle C is exactly the same as the middle C written in the treble clef.

To make music easier to play

Some songs and piano pieces are written in keys that have a lot of sharps, flats and naturals which can slow down your playing and tax your brain! It can be easier to transpose them into a new key.

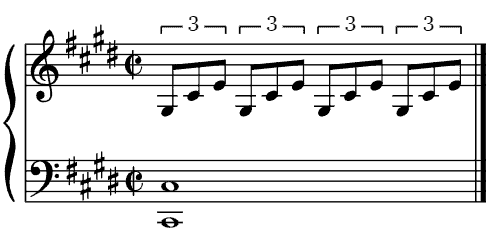

Let’s take, for example, Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata. The original is written in the key of C# minor (which has 4 sharps). Here is the opening of the original:

So that is how Beethoven originally notated this beautiful piece of music. The first two keys in the right hand are G# and C#. It can be tricky for piano players who don’t have much experience to remember which notes are sharps and even the hand position is rather advanced.

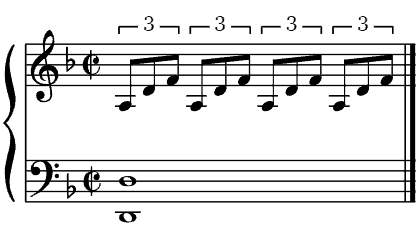

Let’s consider changing this snippet of Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata into a new key that makes it easier to play. Let’s transpose to D minor, which has the key signature of b flat. The key of D minor is one whole step higher than the key of C minor, therefore each note will need transposing one whole step higher, but none of them are sharp or flat, so they are white notes:

If you want to play this very famous piece of piano music in the easier key of D minor, try Skoove’s lesson on Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata!

So piano can accompany transposing instruments

If you are playing the piano and you want to play a piece of music with a clarinet player, the clarinet player will be playing in a different key to you, so that you sound in the same key. For instance, when you play middle C on the piano, the clarinet player reads and plays a B flat but it sounds middle C.

Some other instruments play in different keys too. The pitch you play on the piano is called concert pitch.

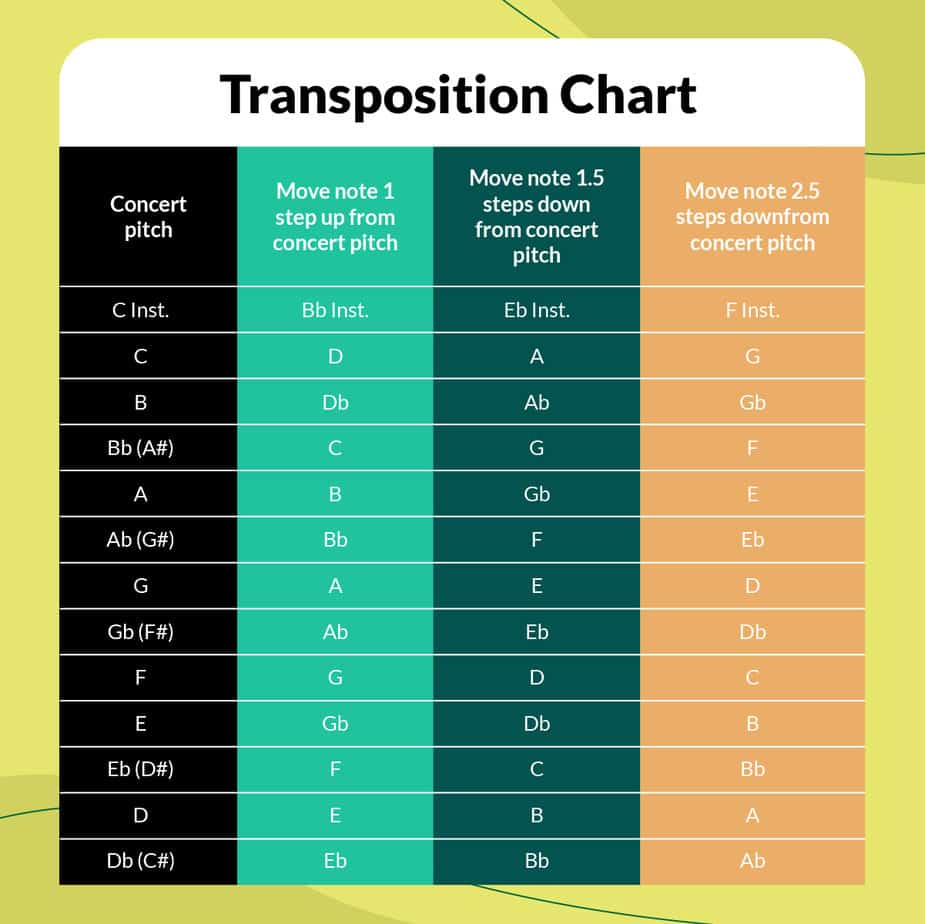

Music transposition chart for transposing instruments

The following chart shows the transposition in music needed for some of the most common transposing instruments:

How to transpose music

Transposing music isn’t quite as daunting as it might at first seem in you follow this three step procedure.

Transpose the key signature

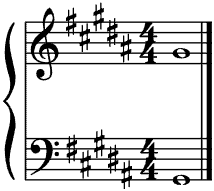

If you need to transpose a piece, first work out the key that you’re starting in. Here is the key signature of G# minor on the grand staff in music, with the tonic note:

The key signature here is G sharp minor, with five sharps.

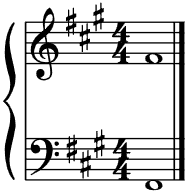

Next, work out how many half steps you need to move up or down to get to your desired key. Let’s say our singer wants each pitch two half steps lower than the music is currently written. This means we work out the key that’s down two half steps (a whole tone), which would be F sharp minor. The new key of F sharp minor has three sharps:

Transpose the notes

Notice that the tonic notes have also moved down one whole step. Once you have decided on your new key signature you can start to write out every note, using the same rhythm as the original, moving each one down a whole tone. Or think of it as two semitones if that makes more sense to you.

Check the accidentals

Once you have every pitch in place, it’s time to check the accidentals. Anywhere a piece of music has an accidental, the transposed music is going to also need an accidental of some kind. Check carefully as it’s not always the same accidental as the original. Maybe a note that’s flattened in the original needs a natural instead in the new version. Think about whether it needs to be raised or lowered, take into account your new key signature and work it out from there.

An example of how to transpose music

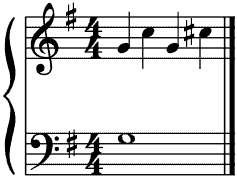

Check out this measure in the original key of F major:

And now look at it transposed up one whole tone into the key of G major:

Notice that the fourth pitch is raised a half step in the key of F major by raising the b flat to a B natural. However, transposed into the key of G major, the fourth note is raised a half step by inserting a sharp accidental – to get the same interval between the notes.

The time value of the notes do not change in a transposition. The time value of the top notes stay quarter notes and the bass note remains a whole note. Just the key signature and the pitch of each note changes.

Transposition range

Transposition can be within the range of up to an octave or down to an octave. When writing transposition, it’s usual to keep as close to the original key as you can when you transpose music.

For instance, if you are in the key of C major and you want to transpose to A major, you can transpose up 9 semitones which is quite a big jump. Or you can transpose down 3 semitones (i.e. a minor 3rd) which is easier to do.

However, if you are transposing at sight it’s not so important whether you go higher or lower depending on your capability on the piano. Remember that if your original is in a major key, you will be transposing it to another major key. Likewise, if it’s in a minor key you’ll be transposing it into another minor key so that the tonality of the song doesn’t change.

The point of transposition is to keep the song sounding the same, but higher or lower in pitch. Modulation is a change of key within a piece of music, usually to create a build or emotional momentum.

Final word

Remember that transposing is always an option if you find a key signature difficult to play or sing. As long as the intervals between the notes are the same as the original, your song will sound the same.

It’s really good to transpose music at sight during your daily piano practice as the more you do it, the better you’ll get at it!

Author of this blog post:

Georgina St George has been playing piano most of her life. She has a thriving piano school on the south coast of England. She loves to infuse her students with her passion for music, composing and performing. Her music has been featured on over 100 TV shows and her musicals have been performed in New York and London’s West End.