Have you ever wondered how musicians effortlessly create melodies and harmonies, or what is a scale degree? Scale degrees are fundamental to grasping music theory, helping you understand the structure of music more efficiently. A scale in music theory is a sequence of notes played in ascending or descending order with a specific interval structure. Scale degrees give names to these notes so you can understand their function. They give musicians a structure, allowing you to utilize and memorize melodies and chords with ease. In this article we will take a look at the fundamentals of scale degrees and how to use them in your piano playing. Let’s dive in!

What are scale degrees?

Every scale can be understood in terms of its scale degree names. Scale degree names are a method of describing the functions of notes and chords in a scale through numbers and labels. The concept may sound complicated, but it is actually quite simple once you get the hang of it.

7 technical names of scale degrees explained

Understanding the seven technical names of scale degrees is essential for learning how melodies and harmonies work. Each scale degree has its own function and shapes the sound and feel of a scale. The scale degree numbers also have names to help you understand their function.

- Tonic: The first degree of the scale and serves as a point of stability and resolution.

- Supertonic: The second degree of the scale. It often leads smoothly to the mediant or dominant.

- Mediant: The third degree of the scale and helps define whether a scale is major or minor.

- Subdominant: The fourth degree of the scale and builds harmonic movement towards the dominant.

- Dominant: The fifth scale degree. It creates a strong tension that naturally wants to resolve to the tonic.

- Submediant: The sixth scale degree and often acts as a bridge between the tonic and dominant.

- Leading tone: The seventh scale degree. It creates a strong pull toward the tonic for resolution.

By recognizing these scale degrees, you can gain a deeper understanding of how melodies and harmonies interact, making your playing and composing more intuitive and expressive. Check out one of our tailored lessons on scales.

Let’s have a look at these scale degree explained in further detail:

Tonic

The tonic is the first degree of the scale. Every scale has a tonic, whether it is the natural minor scale, the A major scale degrees, or the minor pentatonic scale degrees. The tonic note defines the name of the scale and also serves as the tonal center of gravity for the scale. In other words, it is the note that serves as the natural resolution point for all other notes in the scale, whether we are thinking in major scale degrees or minor scale degrees.

Supertonic

The supertonic is the second degree of the scale. Not every scale has a supertonic. For example, a scale like the minor pentatonic scale does not have a second degree. Therefore, there is no supertonic in the minor pentatonic scale. However, many scales included the supertonic, or second degree, so it is useful to understand.

Mediant

The mediant scale degree is the third degree of the scale. Mediant derives from the Latin word for middle. The third scale degree is not the middle of the scale but it is the middle of the triad built on the first degree. All major and minor chords have a mediant, or middle note.

Subdominant

The subdominant is the fourth degree of the scale. An easy way to remember this scale degree name is that it is one note below the dominant. Hence the name subdominant. However, the real meaning of subdominant lies a little deeper. As you discovered earlier, the fifth scale degree is called the dominant. The fourth scale degree is actually a perfect fifth below the tonic. Hence, the name subdominant.

Dominant

The fifth scale degree is known as the dominant. The fifth scale degree is generally considered the second most important scale degree. Most classical music is based on the resolution of the dominant to the tonic. The resolution is also extremely common in pop and contemporary music genres.

Submediant

The sixth scale degree is called the submediant scale degree. The term submediant shares the same source as the subdominant. The sixth scale degree is a third (mediant) below the tonic, hence the name submediant, or lower mediant.

Leading tone

In the major scale, or any scale with a natural seventh scale degree like the melodic minor scale or the harmonic minor scale, the seventh scale degree is known as the leading tone. The leading tone is a half-step lower than the tonic and has a natural gravity to resolve to the tonic.

In scales with a lowered seventh degree, like the natural minor or the blues scale, the seventh scale degree is called the subtonic. This is true for these minor scale degrees. The subtonic is a second below the tonic, like the supertonic is a second above the tonic.

How to find and understand scale degrees?

The most basic way to understand scale degree names is to begin with one of the most fundamental scales in piano: the C major scale. The C major scale is often considered a blank slate to work with in piano music theory. It is neutral and easy to work with.

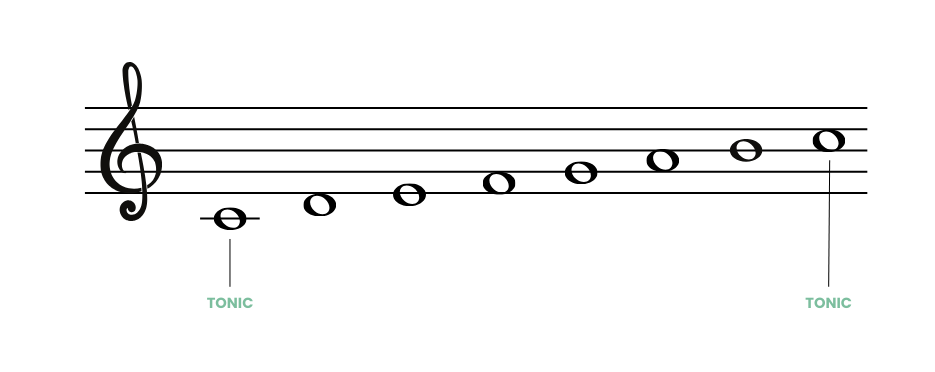

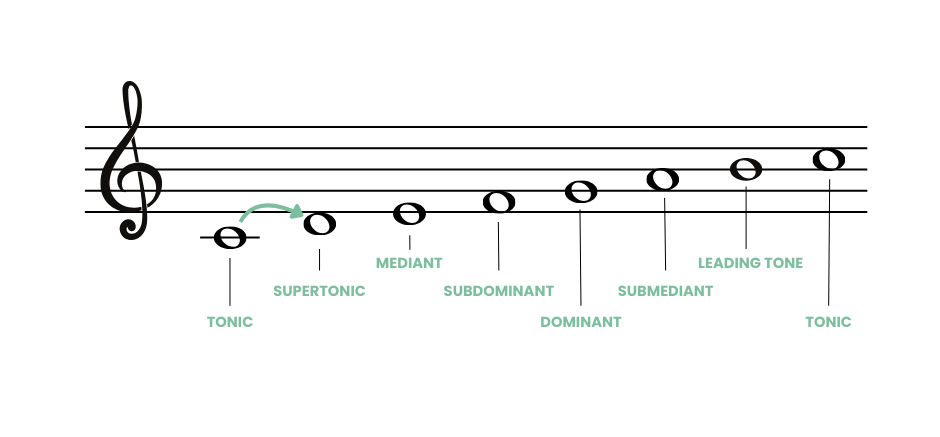

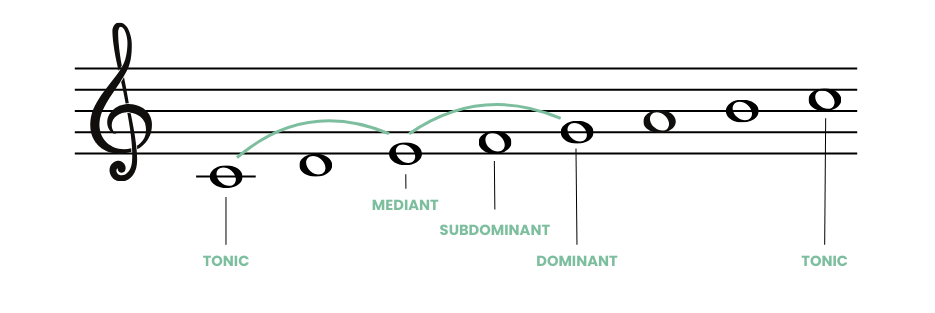

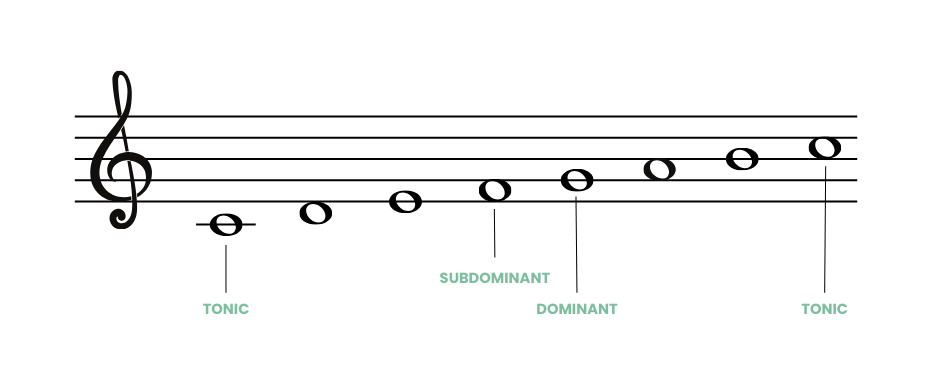

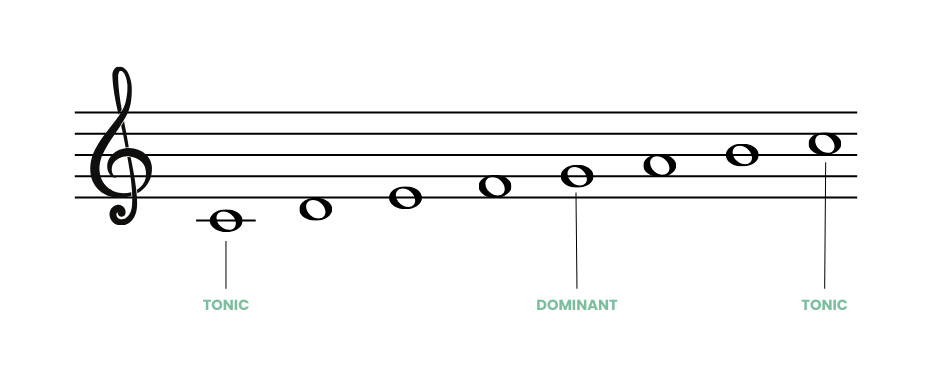

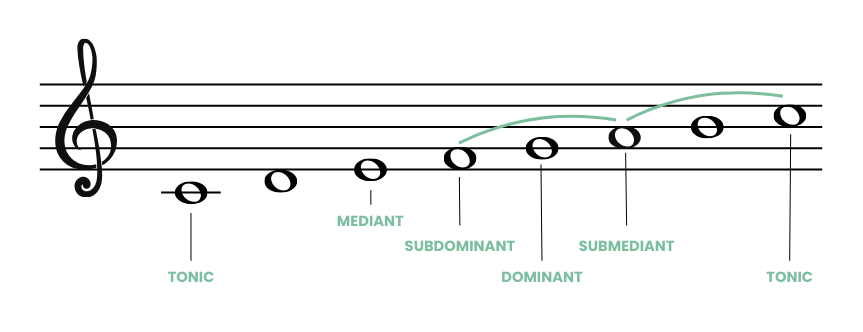

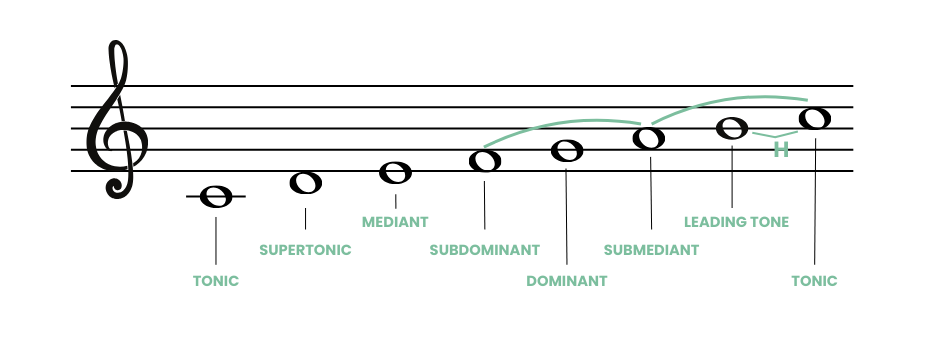

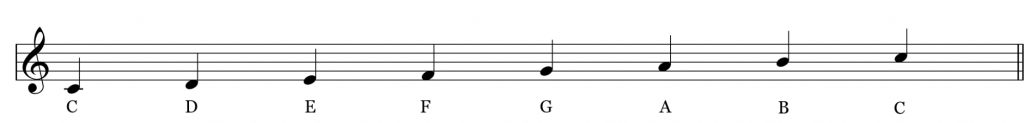

The C major scale is spelled: C – D – E – F – G – A – B – C. Check it out this basic piano scale notated here in treble clef:

In the C major scale, the major scale degrees are as follows:

- C is the first degree of the scale. The first degree is the tonic.

- D is the second degree of the scale. The second degree is the supertonic.

- E is the third degree of the scale. The third degree is the mediant.

- F is the fourth degree of the scale. The fourth degree is the subdominant.

- G is the fifth degree of the scale. The fifth degree is the dominant.

- A is the sixth degree of the scale. The sixth degree is the submediant.

- B is the seventh degree of the scale. The seventh degree is the leading tone.

Common scale degree patterns and their uses

If you understand scale degree patterns you can recognize melodic structures, improvise and compose music more effectively.

Chord patterns:

Scale degrees show us how to build chords by indicating which notes to use within a key and how to build chords from them. The most common chords are made from the 1st, 4th, and 5th scale degrees (I, IV, and V chords, in a major key). Roman numerals are used when describing chords based on their scale degree. Upper case means major and lower means minor.

For example:

- In C major: C major, F major and G major.

In a minor key, the i and iv and chords are usualy minor with major V to keep the tonic to dominant resolution.

For example:

- In A minor: A minor D minor and E major.

Understanding how scale degrees relate to chord progressions makes it easier to recognize patterns, play chord progressions and create music.

Here are some common patterns and how they are used:

- 1-4-5 Progression: The tonic, subdominant and dominant create a sense of movement and resolution.

- 2-5-1 Cadence: This pattern creates smooth harmonic transitions. It’s essential for chord progressions.

- 3-6-2-5-1 Sequence:These chords provide a strong sense of direction and anticipation.

- 5-1 Resolution: One of the most used movements in music. It leads from tension to release.

These patterns work in both major and minor. Make sure to keep the notes within their minor scales and make the V (5) major to keep the tonic (I/1) to dominant resolution sound. Try it out for yourself.

Scale patterns:

Two of the most common scale patterns in music are the major pentatonic scale and the minor pentatonic scale. These five note scales get rid of two scale degrees, creating a distinct sound that is common used in a variety of genres.

- Major Pentatonic Scale: This scale consists of the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 5th and 6th scale degrees.

- In C major: the notes would be C – D – E – G – A.

- It omits the 4th and 7th degrees.

- Minor Pentatonic Scale: This scale consists of the 1st, 3rd, 4th, 5th and 7th scale degrees of the natural minor scale.

- In A minor: the notes would be A – C – D – E – G.

- It omits the 2nd and 6th degrees.

A quick key to create pentatonic scales using scale degrees:

To find a pentatonic scale in any key, start with the major or minor scale and select the appropriate scale degrees:

- For a major pentatonic scale, take the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 5th and 6th degrees.

- For a minor pentatonic scale, take the 1st, 3rd, 4th, 5th and 7th degrees (of the natural minor scale).

By practicing these patterns in different keys, you’ll be able to recognize them in music you play and compose.

How do scale degrees relate to solfege?

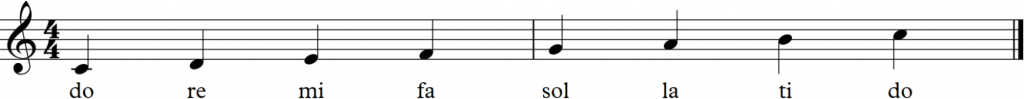

The solfege scale is a syllabic system for note recognition. The solfege scale is a useful way to remember the scale degrees and because they are directly tied to the voice, they help to root the sound of each scale degree physically in your throat and ears.

- The first degree is Do (tonic)

- The second degree is Re (supertonic)

- The third degree is Mi (mediant)

- The fourth degree is Fa (subdominant)

- The fifth degree is Sol (dominant)

- The sixth degree is La (submediant)

- The seventh degree is Ti (leading tone)

Here is the C major scale notated with solfege syllables instead of note names:

There are variations on the solfege scale to account for the flat and sharp notes of a scale, but we won’t cover them here as there are a few different approaches. They are useful when dealing with the minor scale degrees.

Why use scale degrees at all?

After all this music theory, you may be wondering why musicians use scale degrees at all? Good question!

The names of scale degrees allow musicians to break scales and arpeggios down into constituent parts and analyze how the different elements work together. By understanding the names of scale degrees, we can identify patterns and resolutions and then transfer them to other scales. The scale degrees of the C major scale are the same as the A major scale degrees. This consistency allows us to move melodies (transpose) between different keys.

For example:

- You can describe a melody in the key of C major as 3 – 5 – 6 – 4 – 2 – 1 (E – G – A – F – D – C)

- Then use those scale degree names to transfer the melody to another key.

- Using the A major scale degrees, the melody would now be C♯ – E – F♯ – D – B – A.

This ability to transpose expands our musicianship. It allows us to understand the theory behind melodies and chords on a deeper level and allows us to communicate more precisely with other musicians.

Tips for mastering scale degrees

Mastering scale degrees can seem a bit of a drag at first. Like with anything in music it is all about the practice. With some regular practice these concepts will become more familiar. They will also boost your understanding of music as a whole. Boost your music theory skills with these practical tips:

- Daily practice: Try and spend a bit of time each day working on piano scales. Link the notes with scale degrees.

- Learn by ear: Try transcribing some songs and identifying the scale degrees. Trust your ear training.

- Visual aids: Use some charts and diagrams to write scales when you start out. Make sure everything is clear in your mind.

- Play in different keys: Don’t stick to playing C major. Explore more key signatures, see how well you can transpose using scale degrees.

- Sing scale degrees: Using solfege or even just numbers while singing. This helps internalize their function and feelings.

- Practice with backings: Play with backings to hear how scale degrees feel in real music. This is a great way to understand your improvisation more.

- Create melodies: Have fun with scale degrees to compose simple tunes.

Follow these top tips and you will have scale degrees mastered in no time!

FAQ

Why are scale degrees important in music?

Scale degrees are important as they help you understand melodies, harmonize more effectively, improvise confidently and communicate musical ideas through theory more clearly.

Can I use scale degrees to improvise?

You can certainly use scale degrees to improvise. They allow you to understand which notes naturally fit together and how to play in different keys, making improvisation easier and more musical.

How do scale degrees help with songwriting?

Scale degrees help with songwriting greatly. They allow you to structure melodies and harmonies effectively, making compositions sound more intentional and engaging.

Are scale degrees the same in all scales?

Scale degrees are the same in all scales. While the pitches may change, the relationships between the scale degrees remain consistent across different keys and scales.

Author of this blog post

Eddie Bond is a multi-instrumentalist performer, composer, and music instructor currently based in Seattle, Washington USA. He has performed extensively in the US, Canada, Argentina, and China, released over 40 albums, and has over a decade experience working with music students of all ages and ability levels.

Published by Lydia Ogn from the Skoove team